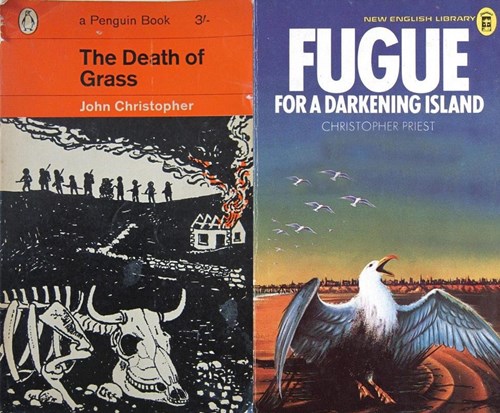

Behaviour and drifts in "The Death of Grass" and "Fugue for a Darkening Island". Previous models for dystopia today.

As the Brexit deadline and a new variant of Covid-19 created the most miserable cartoon of an island prison, there were two books that could objectively claim the prize for 2020: John Christopher's The Death of Grass and Christopher Priest's Fugue for a Darkening Island. Neither, of course written in 2020. Fictionalising current affairs has a tendency to create mythic specimens as fleeting as a mayfly. Perhaps 2020's imprinting events might better be observed from older speculative models. Such an approach could more accurately extrapolate the psychological fallout from the frightened noise of the present – better than any plague diary splotched in the poor light of the lockdown. After all, with this year's crash course in epidemiology, and our foundation in the mathematics of the exponential curve, we all know the future plot is a ghost measurement based on the certainty of past figures.

The Death of Grass by John Christopher, published in 1956, was at the time, a new strain of post-apocalyptic sci-fi, speculating on the consequences of a crop virus called Chung-Li. Originating from China, Chung-Li results in a pandemic affecting all strains of grass. Global harvests fail and the deep psychic nightmare of famine becomes a reality. The surface narrative describes the attempt of a family to escape to a relative's Cumbrian farm, sitting in a geologically protective gill, sustained by a considered decision to grow virus-safe root vegetables. The book though really concerns humanity's reaction to the virus. One that may not attack the human body per-se but that attacks the base neurological needs of a perceived Maslowian pyramid, a direct probe into the limbic. A comic parallel of which has most recently been witnessed in the mad scramble for towers of toilet rolls along the supermarket aisle. Dignity at its most soiled.

Fugue for a Darkening Island imagines a civil war, raging in the UK, precipitated by an influx of refugees from Africa, this in turn, following localised nuclear conflicts on that continent. The book has become a cautionary tale of sci-fi sociology in itself. Originally published in 1972, author Christopher Priest revised the novel in 2011. This was an attempt to tweak the work's political interpretations in the face of suggestions of racism levelled at the book during the intervening 40 years.

Priest's intention, in smoothing its edges, sadly seems to have yielded quite the opposite reaction for some readers. A casual glance of Amazon reviews from recent years is troubling. One 5 star rating from December 2016 proclaims the book to be, “A foretelling of todays [sic] migrant invasion”. The same reviewer finds Peter Hitchens' The Abolishment of Britain “well worth a read”, 5 stars. Another reader discovers the book to be, “a haunting and increasingly prescient narrative which becomes more relevant every day”, 5 stars – but elsewhere on their review list is less than completely overwhelmed with the layout of Osprey Press' Kriegsmarine U-boats 1939-45 vol 1, only 4 stars. For an American reader in 2015, Priest's book “will show how the Islamic caliphate is the greatest existential threat to humanity ever in today's world”.

Then again, my snorkelling through the internet's vast oceans of verbal diarrhoea to an illustrate author's failings, only spoils the evidence, and sullies the stalker.

I'd imagine Christopher Priest would wince in despair at these readings repaving the path to hell from his best intentions. Priest voted Remain in the 2016 referendum. Having worked in the court system for two decades, he is “thoroughly versed in the importance, subtlety and civilizing quality of the European Convention on Human Rights... [having a ] profound and desirable effect, if largely unrecognized and sometimes misunderstood, on many aspects of daily life in this country”. There's a sober post on his website discussing the disastrous referendum.

Though the following piece was intended as a compare and contrast between the behaviours and drifts of the main protagonists in these two books, studying the very different animals of their characters and narratives provides some clues to model 2020's plague community; isolated by disease or xenophobia. The white cliffs at Dover ever more looking like the sombre mortuary isle of Arnold Bocklin. But it's not just in the Garden of England that the supply chain chaos and new variant of Covid conspire into sovereign horror, the mass exodus from London on the eve of tier-4 was the inevitable hubris of capital arrogance. An “Escape from London” that evokes the arpeggiated tension of a John Carpenter soundtrack: once a culture drunk nightclub, by 2021, a boarded up financial prison.

It's telling that both The Death of Grass and Fugue for a Darkening Island play out their opening gambits along the checkpoints of the North London perimeter. The frightened flock, just before this Christmas, beneath the departure boards at Euston and St. Pancras resolutely stood in the rehearsed stage positions of Penguin Classic catastrophes. An instantly recognizable mumuration of worried birds concertinaed through automatic barriers. There's an anxious belt in our metropolitan gut-brain as old and grumbling as the North Circular.

Alan Whitman, the malcontent and amoral chief protagonist in Fugue for a Darkening Island lives with his wife and daughter in Southgate, a nondescript node at the end of the Piccadilly Line:

The words of the UN official came to mind as I drove along the North Circular... Just west of Finchley I had to stop the car and refill the tank with petrol. I was intending to use some of the petrol I had put by as a reserve, but discovered that during the night at the UN camps two of the cans had been emptied... We reached the end of out street a few minutes later... the barbed-wire barricades were still there. On the other side of the road, mounted on the top of a dark-blue van, was a television camera...

These three terse and affectless sound bites from Fugue for a Darkening Island's jump-cut narrative are astute signposts to approaching mid '70s economic strife, in the wake of the Oil Crisis. Familiar avenues, collaged with the more dramatic road furniture of political chaos. In a way these sentences are the urban billboard to the bucolic disruption of Peter Kennard's Haywain with cruise Missiles. They also demonstrate an effective method to evoke the immanence of an localised apocalypse: not by red panoramas of torture, or the quartered limbs of Goya, but by montaging the nihilism of the normal. In a larger arc Christopher Priest does similar montaging throughout his book, cutting from Alan's early life, his pathological philandering at academic conferences to the anarchy, in the midst of civil war, as Alan barters food for sex in a rebel camp.

The Death of the Grass's evacuation from London breathes heavy from the cordite and rubble of WWII. The echo of the air-raid siren and the government brogue of the baffle board radio address. The same roads, though more like those weirdly colourised Pathe newsreels than a fly-postered Protect and Survive satire:

The two cars drove north again, across the North Circular Road, and through North Finchley and Barnet. The steady reassuring voice on the radio continued to drone out regulations, and was then followed by the music of a drone organ... They met the road-block just beyond Wrotham Park. Barriers had been set up in the road; there were Khaki-clad figures on the other side.

The families are fleeing in different directions, the Whitmans to Bristol, John Custance, his family and small entourage to Westomoreland (Cumbria today). Both directions provide convenient cardinal points to trace the main routes to disaster.

Set a generation and a half apart, it's worth looking at another setting of bearings, the moral compasses of the chief protagonists in these two books. Not only in how they reflect the mores of their age, but also the emotional zeitgeist of genre fiction and shifting values within their respective narratives. John Custance begins his quest to escape London to his brother's farm in Westomoreland, a man of post-war decency. An architect by profession, as trustful as the steel girders he oversees for the building of a new Britain. As straight as the crease in tailored trousers, working to support two children at boarding school, in the duty to ever better themselves. This is methodical England, perfect draughtsmanship, as optimistic as a LNER poster – no intrusions of the subversive on his canvas. Custance ends his quest, a Mad Max of the Great Northern Road, Rambo of the Yorkshire Moors, Cain of the Cumbrian gill. In the span of a couple of weeks. With The Death of Grass, John Christopher was adamant to describe a deliberate reaction to the “cosy apocalypse” of John Wyndham's Day of the Triffids, where the main protagonist's stiff upper lip is maintained throughout the voracious green hyperbole. Morals tested and shown to be fixed. The stiff upper lip quivers in Christopher's vision, then the nostrils flare, the animal teeth bare and the feral and amygdalal survival centres take over. As the grass dies, England becomes as egalitarian as a parched Serengeti, and Custance, the Darwinian specimen of a pride of desperate Lions.

A decade and a half-later, Christopher Priest demonstrates a different breed of sci-fi man. Alan Whitman is an unconscionable predator even before the disaster. There's no moral decline as he moves from his job as a university lecturer to factory work as the economic crisis worsens and finally as he scavenges among the corpses on the south coast. Alan is cut from the cloth of the zeitgeist sci-fi, The New Worlds man, an English assassin waiting the scene shift from the ziggurat faculty to the burnt out helicopter. Both Whitman and Custance are perfectly armoured to survive their respective disasters. Custance's muscle memory comes from the war and the boy scout manual: sputtering engines are effortlessly fixed, fish are baited and farmhouses sandbagged against pillaging hordes. Similarly, Whitman has transferable skills learned from the lunch queue chat ups at the academic conference. He oozes his way like a cold reptile into the bed of a fellow attendee, a lecturer from the UEA. A clinical night move carried out as an influx of Afrim refugees land near Gravesend, on the Thames Estuary. Post coital pillow talk of the worsening crises. Another collage of the tawdry mundane and the news bulletin. Later, with his fellow scavengers he enters the encampment of New Forest warlord, swapping provisions for sex with the slave concubines. An agreement is bartered with the leader, and Alan is ushered to a small tent. There, as he takes one of the prostitutes, his foot touches the cold steel of a rifle. He pushes it away under the flap of the tent and goes through the motions. Post coital booty, that he collects later. He's the perfect man-machine practised in the double life from adulterous afternoon hotel to nights in the Joy Division.

In a sense, the psychic stasis of Alan Whitman and the accelerated return to barbarism of John Custance mirror the relative success in their desired geographical trajectories. Custance and his entourage, sharp shooting improvisers from make do and mend generation, despite their ever increasing baggage of refugees, achieve their aim. Along the Great Northern Road, that once manicured causeway to freedom, later on foot, across the moors, they arrive at David Custance's farm in a mythic valley like post-civilisation Argonauts. Homers of an English Odyssey staving off the ogres of famine. John Christopher famously fictionalised the green idyll in Westomoreland, fed by a River Lepe. On oddly allegorical finesse on an otherwise accurate OS Map previously pinpointed with an orienteers detail. It's clear that Christopher scouted his imaginary trip. The tiny market town Masham becomes the key stage for a cry of No pasarán! as North Yorkshire descends into feudalism. Custance and his convoy meet a roadblock as they corner towards the town. A tweed suited Napoleon of a new tribalism orders them from the cars, and they are stripped of all useful booty, forced to the moors on foot. Again it's the minutiae of the AA atlas the gives this dark scene its plausibility. It's the Bronte country souvenir biscuit tin, scratched over with jagged wires of a sectarian checkpoint. All these carefully plotted routes make the River Lepe more significant.

Robert Macfarlane suggests that John Christopher's Lepe is kenning for Lethe, the mythic river of forgetfulness that flowed into the Greek underworld. It is certainly the book's most elusive and fluid cipher on an otherwise rugged terrain of story telling, but it's also the life loop of the plot. A rainbow of tragedy over the boys own holocaust. In the book's prodrome, there's a scene where young John is floundering in the river on a childhood escapade. He survives only by discovering a ledge of stones running through the middle of the treacherous current. The farm is the family home, John will one day leave for the racing future of capital, David to remain in the eternal bucolic of the valley. And in the nocturnal end reels, similar in a way to Coppola's Willard, John remembers the hidden ledge, using it to manoeuvre up river to assassinate his brother. David, now a Cumbrian baron, protector of his rich valley and tribal family.

Where Custance's journey is, despite the endless pillaging and ambushes, a sharp arrowhead toward barbarism, Alan Whitman's peregrinations are as directionless as his identity – opportunistic and shifty yet strangely fit for purpose. The cover of the New English Library edition of Fugue for a Darkening Island shows a squalling seagull, spattered in oil, on a red beach, a ruinous urban outline in the distance. In many way this is Whitman, an indigenous kleptoparasite, wandering the south coast, caked in the sewage of a collapsed country.

Whitman's intention, as previously mentioned, is to take his family to Bristol. Rather than a return to the green bosom of the hearth and home, Whitman's escape starts off as a parasitical venture and continues in a feckless and spiritless manner. In the tradition of the miserable sitcom and kitchen sink, it's in the in-laws that live in Bristol. The academic Lothario quite content to cower in the spare room of his contempt. If Custance is somewhat of an Action Man toy of moral fibre, then Whitman is more accurate than we'd like to admit. He's a thousand grumbling malcontents bickering their way down the M4 corridor to weekends of familial sectarianism. Bouquets of Barbed Wire rather than sandbagged road-blocks, Fugue... is a strangely soap apocalypse. And all the more nihilistic and endogenously depressed as a result.

Alan is a quitter too, their car is stopped at a police checkpoint, not yet out of the magnet pull of London, and they are ordered to proceed only as far as the UN camp at Horsenden Hill in Middlesex.With the Afrim insurgents around, it is too dangerous to travel at night. No shooting their way through the guards of quickly decaying authority, but a moaning obedience to the new order:

Now it was beginning to get dark and were almost as far away from Bristol as we had been when we left home. All three of us were hungry.

No extemporised baiting lines across shimmering brooks for Alan, but a shuffling queue for soup and cigarettes at the prefab refugee camp near Ealing.

Again though it's another generational divide between John Christopher's linear ballistic and Priest's fractured entropy that exacerbates the rudderless amorality of Whitman. The Death of Grass is pre Beat sci-fi, cut from a template of survivalism as traditional as Robinson Crusoe. Priest's, at first seemingly gratuitous jump cut narrative, is an essential amplifier to illustrate Whitman's drifting psyche. Christopher subverts the man of character in the cosy apocalypse to reveal the limbic prepper beneath our civilised suit, but Priest's book is really a study of the characterless. The jump cuts between the refugee camps and the academic conference in Harrogate modern sci-fi stage magic to hypnotise the reader into the mind of the protagonist. In a way, Christopher's ethology is as dog-eared now as the apocrypha of Konrad Lorenz... tattered copies of On Aggression in the sociology section of Oxfam. Priest's espies a new and insidious aggression, even more evident today: the parasitic Alan feeds like a saprophyte in the ransacked midden. The only thing Alan feels is sorrow, for himself...

Unlike the swashbuckling battle between the Custance brothers in the mythic green that encapsulates The Death of Grass's panoramic tragedy, Whitman's endgame is suitably pathetic. Ankle sprained, he hobbles to the barricades in the staunchly defended retirement paradise of Worthing on the South Coast. Pure Brexit defences, all along the white cliffs. Whitman discovers a self-governing, loyalist stronghold to the crown, “....no troops here... we handle our own affairs...” the gruff southern cousin to the Masham chieftain, informs us. This is Farage and Tommy Robinson to the jovial Napoleon of the North Yorkshire moors.

There's something strangely Clockwork Orange about Whitman's temporary salvation. After collapsing in the town centre, he wakes in the soft sheeted spare room of Enid and Charles Jeffrey. He a retired banker, she once a florist. A world like a Sunday Express ceramic plate with all its prim hedges. The chancer sociopath parachuted into the bosom of the cheerfully dutiful. It's also an hermetically sealed world, almost of a model village of an abundant England, and presciently a fantasy of an immigrant free zone. “Don't go around talking about the blacks. That's the main condition of entering the town,” the checkpoint Tommy has already warned Alan.

In a way, this is the fecund sanctuary of John Christopher not run through by a river Lethe but by ignorant bliss. Mrs Jeffrey brings out the indulgent man-child in Whitman – who once operated in the liberal arts faculty. He delights in the fresh bread and succulent fruits she feeds him. The local shops here have a regular supply of groceries, far from the sex bartered booty of the war torn terrains. Again a glimpse into the current fantasy of a self-sufficient post EU farmer's market economy. Whitman worryingly too is seduced into a louche infantilism:

Enid was marvellous to me... There was nothing that was too much to ask of her...She bought me newspapers and magazines... and Mr Jeffrey gave me cigarettes and some Scotch Whisky.

One can almost hear the wide-eyed, post-Ludovico Treatment politeness strategy in Whitman's spoilt glee. But there is actually only one newspaper now in circulation as Enid informs Alan... The Daily Mail. Worthing has become a Truman Show, the sealed biosphere of a cottage fascism. Moreover, to compound the hallucination of an xenophobic idyll, the paper makes no mention of the war, reporting on celebrity gossip and foreign football. More disturbing is the marginalia and metadata around its publication – 12 pages printed twice a week from an address in North France. The true ration in the island Junta is information.

As Whitman recuperates with the “self deluding” Jeffreys we see too the emergence of a far more shaded animal than John Custance's hungry carnivore. We see a sliver of contrition as he recognizes that for too long he has “circuited life on the outer rim”, and seeks to discover his wife and daughter's fate more as an act of redemption than of love. Lazing in the feather quilts of the spare room, Whitman's ruminates too on the political situation. On an intellectual and humanitarian level he accepts the need for a Secessionist movement to ameliorate the Afrim refugees, but on a gut level the repressive and draconian policies of the Nationalist party appeal to his seething resentment and desire for vengeance. The invasion that had deprived him of all he had ever owned. Alan is the most dangerous kind of predator, the irreconcilably ambivalent – as unpredictable as a baited pet. And in this sense, he somehow encapsulates a mollified, once apolitical society and what easy Pavlov's they make in the one newspaper fiction of the Daily Mail Eden.

John Christopher's race into barbarism does come across as unrealistically accelerated. A matter of days before it all descends into the full Grand Guignol of war. The trophy rapes near Doncaster, the summary execution of an adulterous wife within their own faction. As Custance remembers, coming across a ransacked gatehouse:

It was the first time he had seen it in England, but in Italy, during the war... the trail of the looter, but here in rural England. The casual reality in so remote a spot more showed more clearly than the military checkpoints or the winging bombers that the break-up had come irrevocably.

Indeed as one reads The Death of Grass, the inner cinema often overlays the anarchy of Rosselini's neo-realist Rome, an Open City. This all conjures a curious diptych: utopian A roads of the 50s and the empty infrastructure of a collapsed regime. The rapid fire and slightly unconvincing dehumanisation is really precipitated by the author's dramatic narrative decision: that the government intends to drop a hydrogen bomb on Leeds and other northern cities. Partly to quell any uprising but also to secure enough rations following the failed harvests. The ultimate North South divide, a somewhat comical hyperbole to today's geopolitical rift. Priest's Little England, allegorical enclave is more coded and subtle.

In both books though, the climax resolves around the search for hearth and home. Deep down in the vale of soul-making, the ultimate and aching diaspora is the loss of family, no matter how dysfunctional. And both books are notable for the utterly unsentimental destruction at the heart of their campaigns. Christopher's final scene is a brilliantly choreographed tragedy, a fittingly well fashioned poacher's trap. Custance's band meet a heavily guarded turret at the bottom of his brother's gill. David offers John and his family sanctuary, but not the rag-tag baggage of fellow refugees. David is a baron in the new feudal. John returns to his own flock and orchestrates a night manoeuvre. Pure medieval chivalry. John wades up river, the sniper on guard at the raised platform, silhouetted against the silver moon, his brother. A rifle shot to David's forehead, Abel becomes Cain. Replace the high noon duel with the negative plate of a Northern Gothic midnight. A touch too of a gun slinging Catherine Cookson dynastic here. There's also something 1066 about the skirmish. John takes the farm and the land, fates of a nation decided by a single head wound on some lonely field. From Naseby to Battle. The rules as objective as chess, topple the king and take the board.

Fugue's... denouement is as messy as beach of toxic oil. No well demarcated fields in England to fence the battle. Recovered from his sprained ankle, Alan leaves the surrogate Jeffreys and heads for the coastal road. On some miserable shingle bank, he meets a British refugee, waiting for a boat, part of a exodus to Europe. Alan enquires of the Afrim brothels. One recently operated from a nearby stucco Victorian Hotel, now daubed on graffiti, flying tattered foreign flags. Led by the stench, he discovers a midden of female corpses, decomposing and congealing. Dumped together like dead seals, his wife and daughter. That night Alan murders an Afrim soldier and steals his rifle. Replace the meaningless Algerian sands of Camus with the anti-hero of the sci-fi existential. Unlike the fine pincered checkmate of Christopher's ending, Priest's climax is yet more rotting driftwood in a grim continuum.

Prescience and science fiction have become a cliched alliance, a new astrology to constellate the noise of earthly upheavals to cosmic significance. Robert Macfarlane's wise introduction to the 2009 Penguin Classic edition of The Death of the Grass confers its prophetic credentials. Moreover, for Macfarlane, like some diligent soil scientist testing the pH for signs of future catastrophe, “one way to measure the achievement of a novel of this kind is to consider how true its vision becomes, given time”. A bold affirmation, but also a handy branding jingle, and possibly an admission that one day everything will come true. Speculative fiction as a branch of entropy of extruspicy, if we dig around in the bowels of the land long enough.

Obversely, Christopher Priest, prefacing his 2011 revision was perhaps understandably keen to downplay its prescience. An attempt to staunch any wounds opened up by the political ambiguity of the 1972 edition, that somehow Priest was an agitator wild swimming through another mythic current – Enoch Powell's 'rivers of blood' diatribe. It's telling that this preface only a decade old and victim to the ever accelerating geopolitical turn, now reads as wishful thinking. Priest idealistically bathing in his own waters of forgetfulness, recalling Powell's speech:

It was a nasty episode, but it was relatively short-lived. Assimilation soon began, and by now is complete.

Priest is explicit in pointing out in terms of societal hardware and structures, that his 2011 revision is not an update and now serves as a haunted memory of the future:

[T]here were no emails, no DVDs, no internet, no DNA testing, no mobile phones... Britain had not yet joined the EU, the euro had not been invented.

Britain joined the Common Market on 1st January 1973, it left this week, victim of the kind of fantasies described in the Worthing of Priest's bleak imagination. Which in a way does bestow upon Priest the cloak of a haruspex – watching over the horrible broth in fate's cauldron. Replace the weird sisters on a treacherous Macbethian heath, with Alan Whitman discovering the entrails of hearth and home, as the exodus to Europe gets underway. It's the scene of an entirely pyrrhic victory, not at all the nauseating flavour of prescience that the Amazon reviewers froth over.

But I think an easy rehabilitation by revision of Priest's book is almost impossible given the structural problems at the heart of its design. Alan is a weirdly autonomic character, opportunistically seeking sex. The Afrim brothel is a fatal device that congeals with the libidinal fugue-state of Alan's sexual appetite to create an impossibly reactive mess at the core of the novel. The “darkening” of the island in the title, a calamitous and censurable double entendre. Today this is really a contused isle, wounded by the cyanosis of our own flag. All this said, Priest's book leaves a powerful vapour trail in the psyche and invents a uniquely depressing dystopia, a rarely visited inner-space in science fiction of anhedonia.

It's interesting to note that Priest makes reference to John Christopher's catastrophe fictions as biomarkers for his own novel. Fugue for a Darkening Island is seeded in the soil of Christopher's vision, but both books are essentially of the soil. Some of the most retina burning images in The Death of the Grass come from descriptions of the cankered earth. Though our bodies are somewhat accepted playgrounds for viral life, it's when we envision the land as plague that our true vulnerability as a species is demonstrated. The swish of the streak plate technique on the agar dish magnified to vast forests of disease:

When, in the second week of April, … succeeded by a warm, moist spell, it was a shock to see that the Chung-Li virus had lost none of its vigour. As the grass grew, in fields or highways, its blades were splotched with darker green – green that spread and turned into rotting brown. There was no escaping the evidence of these new inroads.

The world as some kind of bubonic bedsore. If we accept the shared lineage of the soil in both books, one political, the other physical, then it becomes easier to see the pattern between pandemic and xenophobia. Rather than prophecies, per-se, perhaps in the vogue of business and epidemiology, both books are to, varying degrees, exercises in behavioural modelling. The Death of Grass is a wildly exponential and asymptotic adventure whereas Fugue for a Darkening Island a very normal distribution of our tendency to casual cruelty.

In the last days of 2020, an even sharper pinprick of a ominous potentiality threatens to mimic The Death of Grass' disastrous curve. The early voice-overs in the book report on the see-saw battle to control the Chung-Li virus. An antidote named Isotope-717 appears effective, but the virus is rapidly mutating, and in its fifth phase is not only completely resistant to the chemical but also attacks all species of grass. Early variants of the virus only kill rice crops but now rye, barley and wheat, all the staples of our shire are susceptible. We're seeing similar bipolar narratives in our news bulletins – from the no-nonsense ninety year old rolling up her sleeves for the first injection to the ashen faced and hopeless Health Minister admitting that the new Covid variant is out of control, The Death of Grass reminds us that we are living in a real time, first person and urgently active story, but also that hyperbole and conspiracy belongs to Shakespearean psychodrama. Society functions when we pay perennial attention and respect to the grassroots services and adequately resource those who maintain our protecting enclaves.