A book that vitally brings eco-horror from the future pages of sci-fi back to the present.

At the launch of his book The Tangle, in conversation with Miranda Sawyer, DJ and author, Justin Robertson paid homage to his dogs. He noted their wisdom, how they could sense the world in ways that were more insightful than humans. They can time travel with their senses, able to smell who might have been in the room. Thankfully, Robertson takes heed from his animals and their instinctive wisdom in his debut novel. He makes many wise steps. For a start, it is not really a novel, with all the dull concessions to world building, stiff characterisation and forced linearity that entails. The Tangle is a really a collection of interweaving short stories and vignettes, and it works effortlessly as such. The Tangle also surrogates consciousness and mortality to the landscape, it is fiercely animistic. The dead live on in The Tangle. Again a neat move, published in the week of COP26. By accident or design, White Rabbit couldn’t have chosen a more propitious release date, for a book that vitally brings eco-horror from the future pages of sci-fi back to the present.

The book kicks off like a drunk Prime Suspect stumbling onto the set of a BBC adaptation of M R James’ Ash Tree. We see a dissolute female detective, surrounded by boorish and hopeless plod, investigating a spate of murders in some horrible Home County town. A last resort for the wannabe, where a less successful Roger Daltrey might live. Indeed, one of the victims is a fading rock star. Only the perpetrator is inhuman, it is the tangle that is slaying the residents of Caxton.

The titular tangle of the book has its roots in the kind of ubiquitous copse you get in towns that have grown from elder woods. A token concession to the wilderness, dotted around faux-Tudor housing estates, often at the end of a garden, and used as polite boundaries between passive-aggressive neighbours. It’s also the kind of place around which suburban myths are built, rumoured quarries for stashes of mulching porn or psychoactive botanicals. In a way, The Tangle has fed on these small copses of childhood, to create the monstrous vision of Robertson’s book; a space for the trapped imagination to run wild and wreak havoc on all the vile inhabitants of Caxton.

Elsewhere, in The Tangle, we get futuristic sketches, following the lineage of a Caxton family. Here, Robertson displays skill for a kind of telescopic storytelling. We see a society where only unhappiness is outlawed, as Kavendish Jeremiah moves through a London, bleached of character, to the Science Museum in Kensington. He views all the exhibits of technological advancement as strange and useless cult objects. Of course, sci-fi is often strongest when it reveals today’s customs in the raw, from an anthropological distance. There’s a hint of a Black Mirror dystopia in these sections of The Tangle.

What drives The Tangle is Robertson’s style, he wields a sharp metaphor, and where necessary, is able to slip into the hymnal and incantatory in the tradition of Thomas Ligotti. But it’s far from the tortured anhedonia of Ligotti, it is funny. The folk who get their comeuppance are the sketch show, vulgar nouveau-riche. Another neat trick by Robertson. He does for the South and Caxton, what The League of Gentleman did for Royston Vasey. It’s about time we spotted the revolting in the well heeled. Case in point, we see a coked up corporate bonding event heading to the tangle for a hunt. An archetypal tosser boss, who gets his delicious comeuppance from the animals he preys upon.

A vegetable consciousness permeates the tangle, its violent outbursts not only out for revenge, but coming from the trauma of inculcation in community atrocities. A past witch hunt through the woods inveigles nature in its crime; the persecuted are hanged from the trees’ boughs. The tangle remembers the trauma and is forced into recidivist actions. Robertson moves intergenerational damage into the environment. The roots have angry nerve endings.

The Tangle can also be seen as a set of parables, delivered on a modern stage, but having an antecedent: the raucous and violent poems told by Ovid in Metamorphoses. This month saw The Globe Theatre’s production of Metamorphoses, and there’s a kindred vibe watching the play, after reading Robertson’s book. If Eco-Horror is the broad tagline, then hubris is the real concern of The Tangle. Like Ovid, Robertson repeats a lesson we never seem to learn: that nemesis is inextricably attracted to hubris, and the consequences are always unpleasant.

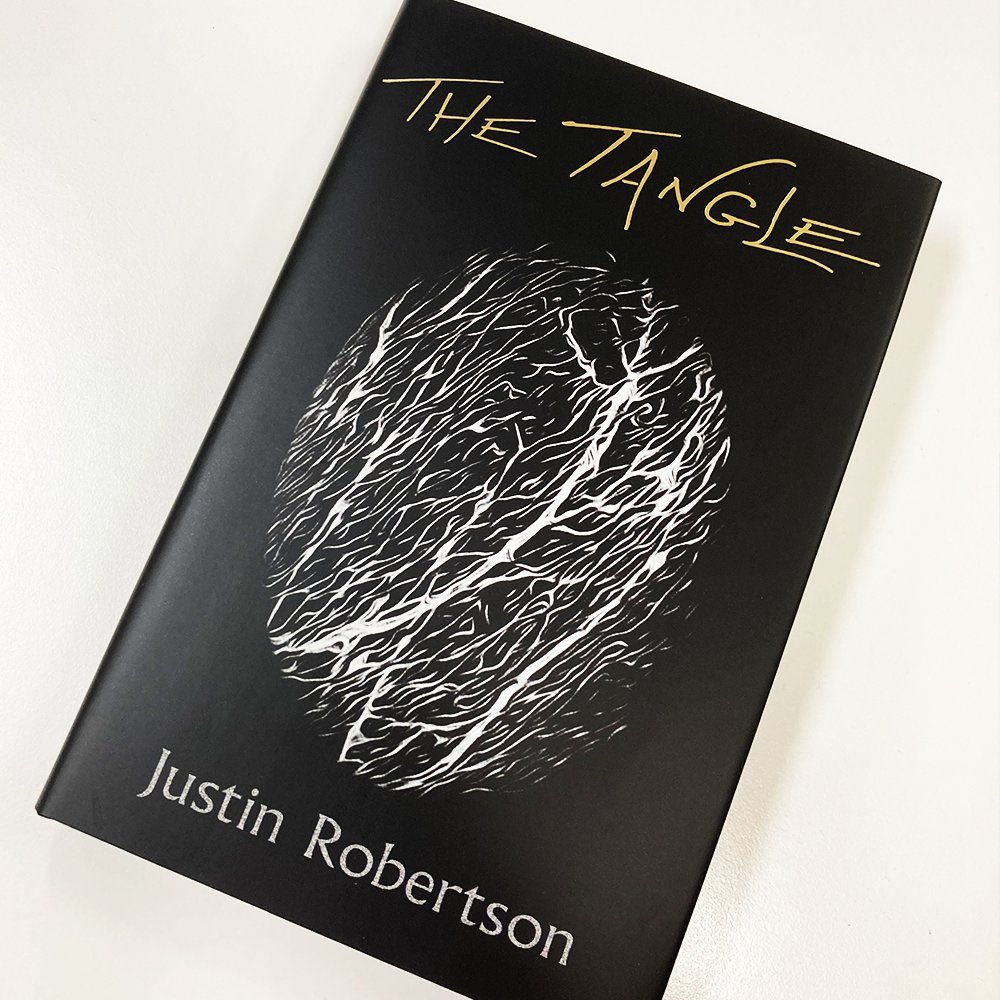

The Tangle, by Justin Robertson is published by White Rabbit